-40%

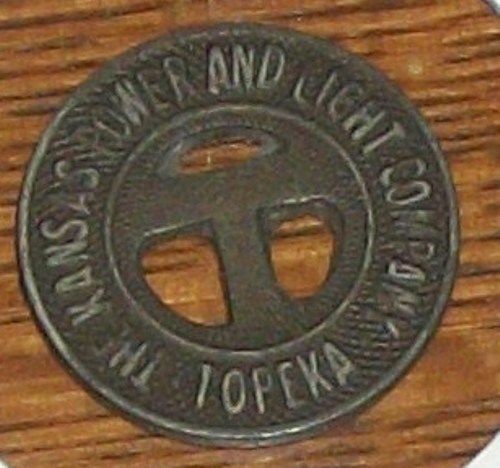

1929 KP&L KS KANSAS POWER LIGHT TOPEKA ELECTRIC TROLLEY TRAIN TRANSIT TOKEN COIN

$ 4.9

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

1929 KP&L KS KANSAS POWER LIGHT TOPEKA ELECTRIC TROLLEY TRAIN TRANSIT TOKEN COIN1929 KP&L KS KANSAS POWER LIGHT TOPEKA ELECTRIC TROLLEY TRAIN TRANSIT TOKEN COIN

1929 KP&L KS KANSAS

POWER LIGHT TOPEKA

ELECTRIC TROLLEY TRAIN

TRANSIT

TOKEN COIN

Click image to enlarge

Description

GREETINGS, FEEL FREE

TO

"SHOP NAKED"

©

We deal in items we believe others will enjoy and want to purchase.

We are not experts.

We welcome any comments, questions, or concerns.

WE ARE TARGETING A GLOBAL MARKET PLACE.

Thanks in advance for your patronage.

Please Be sure to add WDG to your

favorites list

!

NOW FOR YOUR VIEWING PLEASURE…

1929

KP&L

"KANSAS POWER & LIGHT COMPANY"

"TOPEKA"

"GOOD FOR ONE FARE"

ELECTRIC RAILROAD / MASS TRANSIT

RETICULATE CUT COIN

20mm

VG CONDITION

METROPOLITAN AMERICANA

DEPRESSION ERA

SHORT LIVED COMPANY

1926 - 1947

----------------------------------------------

FYI

An electric locomotive is a locomotive powered by electricity from overhead lines, a third rail or on-board energy storage such as a battery or fuel cell. Electric locomotives with on-board fuelled prime movers, such as diesel engines or gas turbines, are classed as diesel-electric or gas turbine-electric locomotives because the electric generator/motor combination serves only as a power transmission system. Electricity is used to eliminate smoke and take advantage of the high efficiency of electric motors, but the cost of electrification means that usually only heavily used lines can be electrified.

Characteristics

One advantage of electrification is the lack of pollution from the locomotives. Electrification results in higher performance, lower maintenance costs and lower energy costs.

Power plants, even if they burn fossil fuels, are far cleaner than mobile sources such as locomotive engines. The power can come from clean or renewable sources, including geothermal power, hydroelectric power, nuclear power, solar power and wind turbines. Electric locomotives are quiet compared to diesel locomotives since there is no engine and exhaust noise and less mechanical noise. The lack of reciprocating parts means electric locomotives are easier on the track, reducing track maintenance.

Power plant capacity is far greater than any individual locomotive uses, so electric locomotives can have a higher power output than diesel locomotives and they can produce even higher short-term surge power for fast acceleration. Electric locomotives are ideal for commuter rail service with frequent stops. They are used on high-speed lines, such as ICE in Germany, Acela in the U.S., Shinkansen in Japan, China Railway High-speed in China and TGV in France. Electric locomotives are used on freight routes with consistently high traffic volumes, or in areas with advanced rail networks.

Electric locomotives benefit from the high efficiency of electric motors, often above 90% (not including the inefficiency of generating the electricity). Additional efficiency can be gained from regenerative braking, which allows kinetic energy to be recovered during braking to put power back on the line. Newer electric locomotives use AC motor-inverter drive systems that provide for regenerative braking.

The chief disadvantage of electrification is the cost for infrastructure: overhead lines or third rail, substations, and control systems. Public policy in the U.S. interferes with electrification: higher property taxes are imposed on privately owned rail facilities if they are electrified. U.S. regulations on diesel locomotives are very weak compared to regulations on automobile emissions or power plant emissions.

In Europe and elsewhere, railway networks are considered part of the national transport infrastructure, just like roads, highways and waterways, so are often financed by the state. Operators of the rolling stock pay fees according to rail use. This makes possible the large investments required for the technically, and in the long-term also, economically advantageous electrification. Because railroad infrastructure is privately owned in the U.S., railroads are unwilling to make the necessary investments for electrification.

History

The first known electric locomotive was built in 1837 by chemist Robert Davidson of Aberdeen. It was powered by galvanic cells (batteries). Davidson later built a larger locomotive named Galvani, exhibited at the Royal Scottish Society of Arts Exhibition in 1841. The seven-ton vehicle had two direct-drive reluctance motors, with fixed electromagnets acting on iron bars attached to a wooden cylinder on each axle, and simple commutators. It hauled a load of six tons at four miles per hour for a distance of one and a half miles. It was tested on the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway in September of the following year, but the limited power from batteries prevented its general use. It was destroyed by railway workers, who saw it as a threat to their security of employment. The first electric passenger train was presented by Werner von Siemens at Berlin in 1879. The locomotive was driven by a 2.2 kW, series-wound motor, and the train, consisting of the locomotive and three cars, reached a speed of 13 km/h. During four months, the train carried 90,000 passengers on a 300-metre-long circular track. The electricity (150 V DC) was supplied through a third insulated rail between the tracks. A contact roller was used to collect the electricity. The world's first electric tram line opened in Lichterfelde near Berlin, Germany, in 1881. It was built by Werner von Siemens (see Gross-Lichterfelde Tramway and Berlin Straßenbahn). Volk's electric railway opened in 1883 in Brighton (see Volk's Electric Railway). Also in 1883, Mödling and Hinterbrühl Tram opened near Vienna in Austria. It was the first in the world in regular service powered from an overhead line. Five years later, in the U.S. electric trolleys were pioneered in 1888 on the Richmond Union Passenger Railway, using equipment designed by Frank J. Sprague.

Much of the early development of electric locomotion was driven by the increasing use of tunnels, particularly in urban areas. Smoke from steam locomotives was noxious and municipalities were increasingly inclined to prohibit their use within their limits. The first successful working, the City and South London Railway underground line in the UK, was prompted by a clause in its enabling act prohibiting use of steam power. It opened in 1890, using electric locomotives built by Mather and Platt. Electricity quickly became the power supply of choice for subways, abetted by the Sprague's invention of multiple-unit train control in 1897. Surface and elevated rapid transit systems generally used steam until forced to convert by ordinance.

The first use of electrification on a main line was on a four-mile stretch of the Baltimore Belt Line of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) in 1895 connecting the main portion of the B&O to the new line to New York through a series of tunnels around the edges of Baltimore's downtown. Parallel tracks on the Pennsylvania Railroad had shown that coal smoke from steam locomotives would be a major operating issue and a public nuisance. Three Bo+Bo units were initially used, at the south end of the electrified section; they coupled onto the locomotive and train and pulled it through the tunnels. Railroad entrances to New York City required similar tunnels and the smoke problems were more acute there. A collision in the Park Avenue tunnel in 1902 led the New York State legislature to outlaw the use of smoke-generating locomotives south of the Harlem River after 1 July 1908. In response, electric locomotives began operation in 1904 on the New York Central Railroad. In the 1930s, the Pennsylvania Railroad, which had introduced electric locomotives because of the NYC regulation, electrified its entire territory east of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

The Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railroad (the Milwaukee Road), the last transcontinental line to be built, electrified its lines across the Rocky Mountains and to the Pacific Ocean starting in 1915. A few East Coast lines, notably the Virginian Railway and the Norfolk and Western Railway, electrified short sections of their mountain crossings. However, by this point electrification in the United States was more associated with dense urban traffic and the use of electric locomotives declined in the face of dieselization. Diesels shared some of the electric locomotive’s advantages over steam and the cost of building and maintaining the power supply infrastructure, which discouraged new installations, brought on the elimination of most main-line electrification outside the Northeast. Except for a few captive systems (e.g. the Black Mesa and Lake Powell), by 2000 electrification was confined to the Northeast Corridor and some commuter service; even there, freight service was handled by diesels. Development continued in Europe, where electrification was widespread.

United States

Electric locomotives are used for passenger trains on Amtrak's Northeast Corridor between Washington, DC and Boston, with a branch to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, and on some commuter rail lines. Mass transit systems and other electrified commuter lines use electric multiple units, where each car is powered. All other long-distance passenger service and, with rare exceptions, all freight is hauled by diesel-electric locomotives.

In North America, the flexibility of diesel locomotives and the relative low cost of their infrastructure has led them to prevail except where legal or operational constraints dictate the use of electricity. An example of the latter is the use of electric locomotives by Amtrak and commuter railroads in the Northeast. New Jersey Transit New York corridor uses ALP-46 electric locomotives, due to the prohibition on diesel operation in Penn Station and the Hudson and East River Tunnels leading to it. Some other trains to Penn Stations use dual-mode locomotives that can also operate off third-rail power in the tunnels and the station. Electric locomotives are planned for the California High Speed Rail system.

During the steam era, some mountainous areas were electrified but these have been discontinued. The junction between electrified and non-electrified territory is the locale of engine changes; for example, Amtrak trains had extended stops in New Haven, Connecticut as locomotives were swapped, a delay which contributed to the decision to electrify the New Haven to Boston segment of the Northeast Corridor in 2000.

(THIS PICTURE FOR DISPLAY ONLY)

---------------------------

Thanks for choosing this auction. You may email for alternate payment arrangements. We combine shipping. Please pay promptly after the auction. The item will be shipped upon receipt of funds.

WE ARE GOING GREEN, SO WE DO SOMETIMES USE CLEAN RECYCLED MATERIALS TO SHIP.

Please leave feedback when you have received the item and are satisfied. Please respond when you have received the item * If you were pleased with this transaction, please respond with all 5 stars! If you are not pleased, let us know via e-mail. Our goal is for 5-star service. We want you to be a satisfied, return customer.

Please express any concerns or questions. More pictures are available upon request. The winning bid will incur the cost of S/H INSURED FEDEX OR USPS. See rate calculator or email FOR ESTIMATE. International Bidders are Welcome but be mindful if your country is excluded from safe shipping.

Thanks for perusing

THIS

and

ALL

our auctions.

Please Check out our

other items

!

WE like the curious and odd.

BUY, BYE!!

Pictures sell!

Auctiva offers Free Image Hosting and Editing.

300+

Listing Templates!

Auctiva gets you noticed!

THE simple solution for eBay sellers.

Track Page Views With

Auctiva's FREE Counter